De-Policing and Death

Does reducing the number of police on the street cause crime to go up?

It would seem obvious, but we at Gun Facts don’t like to assume anything. So we scanned about and found some analysis.

According to two academic criminology papers, the answer is that reducing police presence on the streets absolutely increases homicides, and gun homicides. And it mainly affects poor people of color in major metropolitan areas. This agrees with our “Top 15 Murder Counties” analysis which showed that a lack of policing, and the associated lack of case clearances for homicides, lead to more gun murder.

TAKEAWAYS:

- The mode of de-policing doesn’t matter.

- This hypothesis was tested against:

- Pandemic pullbacks (for public health safety and police outage reasons)

- Pullbacks in the face of the George Floyd riots

- De-staffing via “defund the police” and “criminal justice reform” movements

- The largest impact was in areas normally associated with high street gang activity, and gang crimes rose as much as five-fold.

2020 Was a Hell of a Year

In recent history, the United States has had two substantial and accidental test cases concerning the reduction of police on the streets. The first was a byproduct of both some bad policing (Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota) and police pullbacks. These resulted in police officers not being as engaged as frequently with the community as they used to be (e.g., due to police resentment of public abuse, resignations, defunding). The second was the pandemic, which caused police to withdraw from the streets for health management reasons, as well as many officers being off duty because they became infected with the virus.

With both influences, though mostly associated with the former, there was a dramatic spike in street violence and gun homicides in the year 2020.

Unsurprisingly, the spread of this violence was uneven. To quote one of the papers, “Gun violence increased to a greater extent in neighborhoods with high levels of poverty and minority populations.” Though the authors did not explore that statement more deeply, it aligns with demographics common to communities rife with street gangs and is compelling in and of itself.

Between these two papers 1 2, we see a picture of police officers not being on the streets in already dangerous neighborhoods.

One thing well known about street gang members is that they commit most of their violent crimes in public. A lack of police presence on the streets gives gang members an open playing field on which to commit more violent crime. With police pullbacks from pandemic health management, defunding activities and disincentives, as well as some overly optimistic criminal justice reform activities, net policing in major metro areas declined dramatically in the year 2020.

So, it should be unsurprising that street crime went up in those areas.

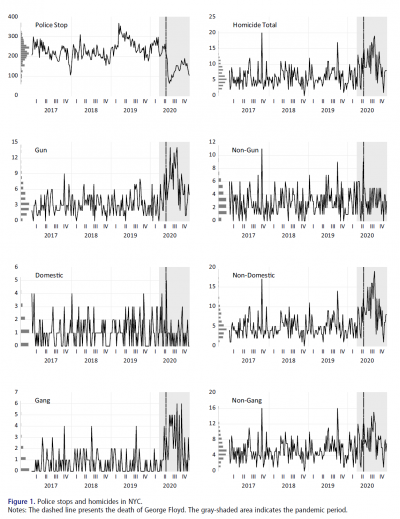

The first study looked at just New York City. Granted, that’s looking at only one major metro area. But the level of detail in the study is quite promising.

There was a drop of almost 50% in police stops in the early days of the pandemic and the riots. During that same initial drop in police activities, homicides spiked by almost double and “gun crimes” went up by more than double. However, non-gun crime remained level. Likewise domestic crimes actually decreased a little bit, while both non-domestic and gang crimes went up significantly.

In other words, crimes in private (where police presence is nonexistent) stayed static, and crimes in public (where police presence dropped) went way up.

In fact, the rate of gang crimes went up as much as five-fold in the initial months of the pandemic and the George Floyd riots.

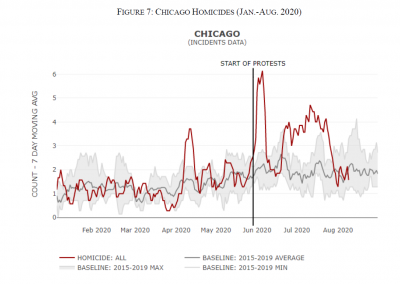

The other paper is much broader. It examines the timing of the George Floyd protest and homicide spikes in Minneapolis, Chicago, Philadelphia, Milwaukee and New York. It also incorporated seasonal adjustments, given the time of year when many of these factors were happening. Importantly, it examined the policing in those specific cities to measure the effects of the policing on homicides.

Minneapolis would be a special case, considering that is the city where George Floyd was killed. But it’s instructive to note that in almost every major metro area where there were George Floyd protests, homicides spiked at the start of the protest. In other words, rioting and public disorder, combined with de-policing and over extension of the remaining police staffing, provided ample opportunity for street crimes and violence to escalate.

The second paper is extraordinary inasmuch as it looked at the timing of both the pandemic police pullback and the George Floyd riot pullbacks, and concluded that had pandemic pullbacks alone been responsible, the spike in homicides would have happened 10 weeks earlier. They did not. They rose almost in lockstep with civil disorder.

Like the other study, this one also notes that nonviolent crimes did not rise during the Floyd riots. Again, this harkens back to the fact that most street gang violence occurs in public, and that gang members took the opportunity of the de-policing – whether from pandemic pullbacks or defunding initiatives – to commit violence in the absence of deterrence.

One of the compounding effects was that police became disenchanted in their careers in the wake of the defunding initiatives and public resentment over George Floyd’s death. For example, the Minneapolis Police department lost at least 100 officers during that era. That already strained police departments were losing officers only exacerbated the situation.

Police Should Be Present and Proactive

What emerges from these studies is that proactive policing – ensuring that police are on patrols in whatever neighborhoods they are needed – is a suppressant to street crime. We’re seeing this play out in select major metropolitan areas (e.g., San Francisco) that endorsed defunding and criminal Justice reform initiatives during the George Floyd era, but that are now reinstituting “tough on crime” programs and ramping up police presences because their street crime rates escalated beyond the public’s tolerance level.

The shame of it all is that this spike in violence, gun homicides, and street crime was highly concentrated in poor neighborhoods populated with minorities. The most disadvantaged people in our country were the biggest victims of de-policing.

Comments

De-Policing and Death — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>