Firearms In The United States

Nobody is sure of exactly how many firearms are in circulation. This stems from a long history of no regulations on firearm ownership. In Gun Facts, we rely on multiple academic resources.

Number of firearms in America: Between 223,000,000 1 and 415,000,000 2

Handguns in circulation: 174,000,000 (2018)

Households with Firearms: Between 40-50%. 3

Individuals who own firearms (age 18+): 31.9%, or 81,400,000 in 2021 4

| Any Gun | 31.9% |

| Handguns | 82.7% |

| Rifles | 68.8% |

| Shotguns | 58.4% |

| AR-15s | 30.2% |

| Magazines > 10 rounds | 48.0% |

For AR-15s in particular, one media survey 5 concluded:

- 20% of gun owners owned one or more AR-15s.

- With 31.9% of adults owning guns, this equates to 16.5 million AR-15 owners.

- The number of AR-15s in circulation is more since people can own more than one.

Gun Ownership by State

| State | Average (households) | Variance (households) | 2013 – Gun ownership and social gun culture – Kalesan, Villarreal, Keyes, Galea – 2015 – Survey 4000 people, YouGov panel | 2002 – Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) |

2021 National Firearms Survey: Updated Analysis Including Types of Firearms Owned; English; 2022 (largest sample, current gold-standard) |

| Household | Household | Individual | |||

| Alabama | 53.1% | 0.3% | 48.9% | 57.2% | 39.6% |

| Alaska | 61.2% | 0.0% | 61.7% | 60.6% | 33.4% |

| Arizona | 34.3% | 0.1% | 32.3% | 36.2% | 32.0% |

| Arkansas | 58.1% | 0.0% | 57.9% | 58.3% | 36.6% |

| California | 19.8% | 0.0% | 20.1% | 19.5% | 25.5% |

| Colorado | 34.4% | 0.0% | 34.3% | 34.5% | 33.6% |

| Connecticut | 16.4% | 0.0% | 16.6% | 16.2% | 20.2% |

| D.C. | 15.6% | 2.1% | 25.9% | 5.2% | 23.9% |

| Delaware | 16.0% | 2.3% | 5.2% | 26.7% | 24.7% |

| Florida | 29.3% | 0.2% | 32.5% | 26.0% | 30.3% |

| Georgia | 36.3% | 0.4% | 31.6% | 41.0% | 37.1% |

| Hawaii | 27.4% | 6.3% | 45.1% | 9.7% | 16.4% |

| Idaho | 56.9% | 0.0% | 56.9% | 56.8% | 54.5% |

| Illinois | 23.0% | 0.2% | 26.2% | 19.7% | 26.5% |

| Indiana | 36.4% | 0.1% | 33.8% | 39.0% | 40.3% |

| Iowa | 38.9% | 0.5% | 33.8% | 44.0% | 33.2% |

| Kansas | 38.0% | 0.7% | 32.2% | 43.7% | 42.8% |

| Kentucky | 45.2% | 0.2% | 42.4% | 48.0% | 46.7% |

| Louisiana | 45.1% | 0.0% | 44.5% | 45.6% | 32.8% |

| Maine | 31.9% | 1.7% | 22.6% | 41.1% | 35.9% |

| Maryland | 21.4% | 0.0% | 20.7% | 22.1% | 21.7% |

| Massachusetts | 17.7% | 0.5% | 22.6% | 12.8% | 15.8% |

| Michigan | 34.6% | 0.7% | 28.8% | 40.3% | 34.7% |

| Minnesota | 40.7% | 0.3% | 36.7% | 44.7% | 32.5% |

| Mississippi | 48.6% | 0.7% | 42.8% | 54.3% | 39.5% |

| Missouri | 36.3% | 1.7% | 27.1% | 45.4% | 39.7% |

| Montana | 56.9% | 0.4% | 52.3% | 61.4% | 48.4% |

| Nebraska | 31.0% | 2.5% | 19.8% | 42.1% | 37.2% |

| Nevada | 34.5% | 0.2% | 37.5% | 31.5% | 38.0% |

| New Hampshire | 22.5% | 1.3% | 14.4% | 30.5% | 24.1% |

| New Jersey | 11.3% | 0.0% | 11.3% | 11.3% | 19.3% |

| New Mexico | 44.8% | 0.5% | 49.9% | 39.6% | 33.8% |

| New York | 14.2% | 0.3% | 10.3% | 18.1% | 22.7% |

| North Carolina | 34.8% | 0.7% | 28.7% | 40.8% | 37.3% |

| North Dakota | 51.1% | 0.2% | 47.9% | 54.3% | 42.6% |

| Ohio | 25.9% | 0.8% | 19.6% | 32.1% | 33.7% |

| Oklahoma | 37.9% | 0.9% | 31.2% | 44.6% | 40.5% |

| Oregon | 33.2% | 0.9% | 26.6% | 39.8% | 38.3% |

| Pennsylvania | 32.7% | 0.3% | 28.8% | 36.5% | 30.3% |

| Rhode Island | 9.6% | 0.3% | 5.8% | 13.3% | 16.9% |

| South Carolina | 44.7% | 0.0% | 44.4% | 45.0% | 40.7% |

| South Dakota | 47.5% | 3.1% | 35.0% | 59.9% | 39.2% |

| Tennessee | 42.9% | 0.2% | 39.4% | 46.4% | 43.0% |

| Texas | 35.8% | 0.0% | 35.7% | 35.9% | 36.0% |

| Utah | 38.6% | 0.9% | 31.9% | 45.3% | 42.8% |

| Vermont | 37.2% | 1.4% | 28.8% | 45.5% | |

| Virginia | 32.6% | 0.2% | 29.3% | 35.9% | 30.6% |

| Washington | 32.0% | 0.4% | 27.7% | 36.2% | 32.8% |

| West Virginia | 56.1% | 0.1% | 54.2% | 57.9% | 53.0% |

| Wisconsin | 39.5% | 0.5% | 34.7% | 44.3% | 33.3% |

| Wyoming | 58.3% | 0.4% | 53.8% | 62.8% | 42.7% |

Here is the core data from three different studies, including an average of their estimates and a variance measure that shows, with a small number of oddities, close alignment.

2,500,500 or 235,700 defensive gun uses (DGU)?

You may have heard that firearms are used 2.5 million times a year for self-defense, and you may also have heard they are only used 235,700 times. The reason is that there are different sources of the data and different ways of measuring.

The 2.5M times number come from criminologist Gary Kleck and his book Targeting Gun. Kleck gathered many surveys from both criminologists and media sources, and the midpoint was 2.5M DGUs a year (one of the surveys he reported was significantly higher and another one was lower, but most were in the 2-2.5M range).

The 235,700 number comes from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). One important methodological difference in the NCVS is that it entails personal, face-to-face engagements with government employees (per their methodology documentation “all interviews are done by telephone whenever possible, except for the first interview, which is primarily conducted in person”).

There is also the potential for self-incrimination that may prevent reporting of some DGUs to this government survey. A victim may have a strong reluctance to talk to a government agent about a firearm brandishing incident (which are 98% of DGUs) because they may not know the act was 100% legal. Thus, to assure they are not victimized by the legal system, they avoid reporting DGUs to this government survey.

Another criticism of the NCVS is that questions concerning gun-use are never asked unless the interviewee first indicates that they were “a victim of a crime.” Since some people who successfully avoid being a victim by using a gun reply that they have not been victimized, they are never asked the question about use of a firearm.

Because of this, some criminologists believe there is a self-reporting bias in the NCVS (e.g., people don’t like to tell the government they own or used a gun). Thus, this low number from the NCVS is considered to be an outlier and not reliable compared to other, broader and more standardized measures.

British Crime Statistics

The U.K. measures crime using two different processes:

British Crime Survey (BCS): The Home Office conducts surveys of the population to determine how often subjects have been affected by criminal activity. Data is projected to reflect the entire population.

Police reporting: Crimes are reported to the police and nationwide, census-level statistics are summarized.

The BCS has been reporting a declining crime rate in the UK while police reporting has shown an increase. The BCS has routinely been criticized because it under reports crime due to the following factors:

- Murdered and imprisoned people do not answer surveys

- Some crimes are not surveyed when victims are below age 16 6

- Crime against institutions (bank robbery, etc.) are not included

The crime reporting system isn’t without flaws either. Crimes are recorded at final disposition (conviction/acquittal), leaving many crimes completely unreported 7

These deficiencies are so significant that even the British government does not believe the accuracy of the BCS.

“[T]he BCS did not record ‘various categories of violent crime’, including murder and rape, retail crime, drug-taking, or offences in which the victims were aged below 16. The most reliable measure of crime is that which is reported to the police. We’re facing over a million violent crimes a year for the first time in history.” 8

Gun control groups tend to cite the BCS reports because it supports their narrative that Britain’s gun control laws lower crime. Criminologists tend to use the reporting system because it more closely matches the FBI Uniform Crime Statistics used in the United States.

More curious are the sudden leaps in reported violent crime when the British Home Office enforced standardized methods for recording reported crime (which led the Home Office to claim crime reports to be of poor quality, and thus rely on the suspect survey mechanism):

The 1998 changes to the Home Office Counting Rules had a very significant impact on violent crime; the numbers of such crimes recorded by the police increased by 83 per cent as a result of the 1998 changes … The National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS), introduced in April 2002, again resulted in increased recording of violent crimes particularly for less serious violent offenses. 9

British Gun Control History

1870: British gun control began with licensing.

1903: Pistols Act to stop people carrying guns, and required a license for handguns outside the home.

1920: Firearms Act 1920 required anyone wanting to purchase or possess a firearm or ammunition to obtain a firearm certificate, and limited ammunition possession. Enabled denial by local chief constables and a “good reason” justification denial grounds.

1937: Firearms Act 1937 expanded age restrictions, transferred certificates for machine guns to military oversight, expanded gun seller regulations, expanded local constable conditions for issuance, ended self-defense as a justifiable condition.

1968: Firearms Act 1968 consolidated all previous laws, added for the licenses. Added license for long-barrel shotguns, safe storage provisions, criminal right-to-possess suspension.

1988: 1988 Firearms Amendment Act banned semi-automatic and pump-action center-fire rifles, military weapons firing explosive ammunition, short shotguns that had magazines, pump-action and self-loading rifles. Add registration and secure storage of shotguns.

1997: Firearms Amendment Act defined and prohibited “short firearms”, effectively banned private possession of handguns.

Gun Violence Archive

There are numerous critiques of the Gun Violence Archives, which combined indicate that this is a non-viable criminology resource.

The primary problem is a lack or reach. Whereas the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting system spans the country, the Gun Violence Archive “… numbers are found through 2,000 LEO, government and media sources.”

There are nearly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. If we were generous and assumed that most of the outlets from which the Gun Violence Archives find incident reports were law enforcement, they are still examining only 11% of the agencies. Since media reports make up a significant amount of the Gun Violence Archive’s reporting, odds are the reach into official agencies, which have uniform tracking methodologies, is much lower than 11%.

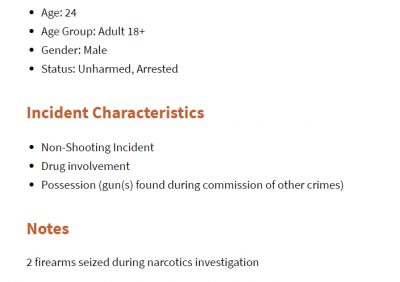

Another problem is the definition of “gun violence” employed by the Gun Violence Archive is often misused. Their definition is “… all incidents of death or injury or threat with firearms.” This leads to episodes like the one shown here, clipped from the Gun Violence Archive web site, being included in their tallies along with homicides and woundings. Notice that this was a “non-shooting” incident.

Another problem is the definition of “gun violence” employed by the Gun Violence Archive is often misused. Their definition is “… all incidents of death or injury or threat with firearms.” This leads to episodes like the one shown here, clipped from the Gun Violence Archive web site, being included in their tallies along with homicides and woundings. Notice that this was a “non-shooting” incident.

The takeaway is that the Gun Violence Archive is a non-serious tool for understanding crime, violence and how guns fit into the situation.

Confused terms in gun control policy

Assault rifle and assault weapon:

Assault rifles are real, and are a specific type of military weapon classified by the Department of Defense. These are not generally available to the public.

Assault weapon is a legislative term, and means whatever the law says. In a paper promoting the extension of the federal assault weapons ban, the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence admitted that various “assault weapons” laws across the nation covered anywhere from 19 to 75 banned firearms, six differing generic classification schemes and several legal systems for banning more firearms without specific legislative action.

“Gun Dealer”

Federal law defines a gun dealer as someone who is “engaged in the business of selling firearms,” which in turn is defined as a “devot[ing] time, attention, and labor to dealing in firearms as a regular course of trade or business with the principal objective of livelihood and profit through the repetitive purchase and resale of firearms.”

The statutory definition explicitly excludes “a person who makes occasional sales, exchanges, or purchases of firearms for the enhancement of a personal collection or for a hobby, or who sells all or part of his personal collection of firearms.”

Negligent discharge and accidental shooting

Negligent discharges are defined as “a discharge of a firearm involving culpable carelessness.” In other words, a person did not have their firearm properly secured or handled it in a careless fashion.

Accidental shootings include negligent discharges, but include other activities such as unintended targets, people walking into a line of fire, down-range hunting accidents and more.

Genocide and Gun Control 10

Outside of war, the greatest loss of human life in the 20th century came from governments. In nearly every case, disarmament preceded mass murder. Though some nations have been functionally disarmed without such atrocities, it is worth remembering:

In 1911, Turkey established gun control. Subsequently, from 1915 to 1917, 1.5-million Armenians, deprived of the means to defend themselves, were rounded up and killed.

In 1929, the Soviet Union established gun control. Then, from 1929 to 1953, approximately 20-millon dissidents were rounded up and killed.

In 1938 Germany established gun control. From 1939 to 1945 over 13-million Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, mentally ill, union leaders, Catholics and others, unable to fire a shot in protest, were rounded up and killed.

In 1935, China established gun control. Subsequently, between 1948 and 1952, over 20-million dissidents were rounded up and killed.

In 1956, Cambodia enshrined gun control. In just two years (1975-1977) over one million “educated” people were rounded up and killed.

In 1964, Guatemala locked in gun control. From 1964 to 1981, over 100,000 Mayan Indians were rounded up and killed as a result of their inability to defend themselves.

In 1970, Uganda embraced gun control. Over the next nine years over 300,000 Christians were rounded up and killed.

Over 56-million people have died because of gun control in the last century

Notes:

- Guns Used in Crime, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Marianne W. Zawitz, 1995 ↩

- 2021 National Firearms Survey: Updated Analysis Including Types of Firearms Owned; English; 2022 ↩

- Survey data from Pew, Gallup, ABC News ↩

- 2021 National Firearms Survey: Updated Analysis Including Types of Firearms Owned; English; 2022 ↩

- Washington Post, Sep/Oct 2022 ↩

- This is a serious omission as most gang crime is committed by and against young people. ↩

- Fear in Britain, Dr. Paul Gallant and Dr. Joanne Eisen, National Review, July 18, 2000 ↩

- Row over figures as crime drops 5%, David Davis, Shadow Home Secretary, The Guardian, July 22, 2004 ↩

- Crime in England and Wales 2005/06, British Home Office, July 2006 ↩

- Death by Gun Control: The Human Cost of Victim Disarmament,” Aaron Zelman & Richard W. Stevens, 2001 ↩