K–12 Shooting Stats

School shootings are reasonably rare, though you would never know if from reading stories in the mainstream media or listening to people who maintain databases of questionable quality.

Fortunately, the federal government did a deep dive into the subject, and from that we come to some interesting conclusions about who is actually in danger at K–12 schools and why it only reinforces what we know about gun violence in general.

TAKEAWAYS

- The most commonly media-cited K–12 school shooting database is overstated by 40%.

- Most K–12 shootings are over disputes that align with inner-city and street gang subcultures.

- School-targeted shootings (which include mass shootings) occur at about half the rate of “nominal” dispute/gang shootings.

- Targeted shootings, because they are planned, come from generalized grievances, and use “cattle pen scenarios,” have a higher body count than the more common one-victim dispute shootings, though the latter occurs twice as often.

What is a “shooting”?

As with anything that has a political angle, definitions are routinely corrupted in order to try to get notoriety in the political marketplace.

Such is the case with the definition of school shooting. In one database 1 which is unfortunately cited by the media without scrutiny, the number of instances of so-called school shootings is vastly overstated. It is interesting that in the government study we review today, they began with this highly questionable database, devised a rational definition of school shooting that conforms to the public’s understanding of what such an event is, and then proceeded to present data that has a basis in reality.

And from that we discovered that the highly suspect database mentioned before overstates the number of school shootings by 40%. How do they do that? Their definition of school shooting is so broad that a stray bullet landing on school ground from a drive-by-gang shooting a block away constitutes, for them, a school shooting. A seriously depressed teacher who commits suicide in her car in the parking lot at three o’clock in the morning is also considered by them to be a school shooting.

In other words, they peddle nonsense.

The report in hand 2 was developed by the General Accounting Office (GAO) and did what good researchers should do – namely, start with a well-reasoned and sound definition of a school shooting. They very specifically define it as “anytime a gun is fired on school grounds, on a bus, during a school event, during school hours or right before or after school.” This excludes events that do not involve students, do not involve faculty, do not involve resource officers, and actually occur when students would be in danger. In other words, it is highly inconvenient for people who want to create panic over K–12 school shootings.

Fortunately, this report distilled the important elements of the data in a way that it’s meaningful to us. Unfortunately, the raw GAO filtered data is locked up, which makes it nearly impossible for independent researchers such as the Gun Facts project to do an even deeper dive. The government may have done well by studying the subject, but they did a grand disservice to the public by not allowing others to second-guess their work and to take it even further.

Be sure to write to your congressperson about this because we at the Gun Facts project are rather ticked off about the situation.

The GAO Report

We’ll start by noting that the origin of the inappropriate database actually occurred within government, at the Naval Postgraduate School, a part of the Center for Homeland Defense. The maintainer of that database has since gone independent, and seems to be hungry for media attention, which unfortunately he actually acquires.

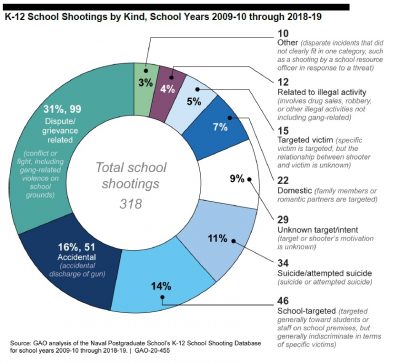

For their exercise, the GAO took the database as last updated by the Naval Postgraduate School and applied their rational definition of what constitutes a school shooting to every row in the database. This led to an end count of 318 school shootings over a 10-year period from the school year 2009–10 through 2018–19.

That comes out to being about 32 school shootings in K–12 institutions every year, or about one K–12 school shooting per state every two years. But it must be noted that this definition of school shooting includes a lot of things which are not a direct endangerment to innocent students.

For example, a full 3% are classified as “other.” This category includes shots fired by resource officers at the school in response to a threat. It also includes 11% that were suicides or suicide attempts, either by students, workers, faculty, or strangers on the campus. As you can see, even our total count of 318 may be grossly inflated. We will continue to use that number during this review, but keep in mind that the situation is better than it appears on the surface.

Though the raw data is not available to us, the breakdown provided by the GAO is sufficient for us to view the three critical elements of school shooters – namely, why they shoot, who does the shooting, and where they do the shooting. It also gives us a little background on the shooters, which leads to an interesting inspection of the intersections of who, where, and why, which in turn leads us back to inner cities and the influence of street gangs.

The “Why”

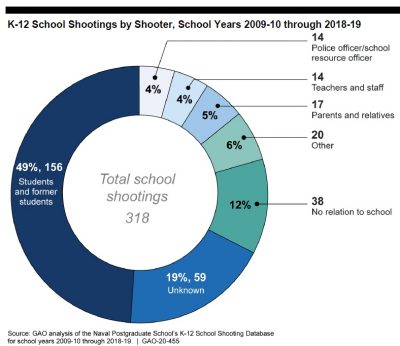

Why people discharge firearms in K–12 schools breaks down along predictable lines. The largest slice of the pie comes from people exercising grievances or disputes; those constitute 31% of all school shootings. We’ll come back to this later because dispute settlement is a hallmark of street gang culture, and we see this exercised far too frequently in K–12 incidents. Given that nearly half of all K–12 firearm discharges were done by students or former students, and another 19% by unknown actors, it’s highly unlikely that most of these discharges were related by authorized carriers. Indeed, the table shows that 8% of discharges were either from police and resource officers or teachers and staff; thus we are not certain if all the teachers and staff were authorized to be carrying.

Why people discharge firearms in K–12 schools breaks down along predictable lines. The largest slice of the pie comes from people exercising grievances or disputes; those constitute 31% of all school shootings. We’ll come back to this later because dispute settlement is a hallmark of street gang culture, and we see this exercised far too frequently in K–12 incidents. Given that nearly half of all K–12 firearm discharges were done by students or former students, and another 19% by unknown actors, it’s highly unlikely that most of these discharges were related by authorized carriers. Indeed, the table shows that 8% of discharges were either from police and resource officers or teachers and staff; thus we are not certain if all the teachers and staff were authorized to be carrying.

That said, the GAO notes that the disputes classification includes gang-oriented disputes. So, they are functionally aware that gang culture and retribution culture within gangs may be a primary cause of the largest segment of K–12 campus shootings. What is unsaid, out of necessity, is that some students may not be gang members, and the shooting might not be a “gang function,” but the student might be a gang associate or simply exercising gang “retribution” culture.

After that, 16% of firearm discharges are purely accidental. There’s not a solid breakdown, without the raw data, to know whether these accidents mainly occurred due to people authorized to have guns on campus, or idiot children who have brought them to school.

Note that these two elements – disputes and accidents – constitute 47% of all K–12 campus shootings. The next biggest group, targeted attacks, which we relate to tragic events such as Parkland High School and Sandy Hook Elementary, are at worst only 14%.

This is where the public is probably getting a mass misperception about K–12 shootings. Most of them are dispute-oriented, which may also mean gang-related. These disputes are over twice as likely to occur than a targeted shooting, and targeted shootings go well beyond mass shootings (e.g., they may target a small number of very specific people instead of the student/faculty body at large).

After that comes suicides, which rack up 11% of these instances. Sad as suicides are, they are not generally endangering to other students. And often these suicides are committed by faculty or staff. So again, it’s not a student protection issue in general.

The other categories are rather nominal, but we’ll note that 3% of what are classified as K–12 school shootings were conducted by “others,” which includes police and resource officers responding to threats. There is no finer breakdown of this number, and the load is so small that a breakdown might be misleading.

The “Who”

Having looked at the why, let’s explore the who.

Nearly half of all K–12 shootings were done by students or former students. That word “former” is intriguing because somebody who is not supposed to be on campus in order to receive an education, but comes on campus to shoot somebody, is a sign of external matters unrelated to the school system. It would be entirely unsurprising to learn that former students, including dropouts, who are associated with or members of street gangs, come on to campus to settle disputes, which are the largest motivation for K–12 incidences.

Nearly half of all K–12 shootings were done by students or former students. That word “former” is intriguing because somebody who is not supposed to be on campus in order to receive an education, but comes on campus to shoot somebody, is a sign of external matters unrelated to the school system. It would be entirely unsurprising to learn that former students, including dropouts, who are associated with or members of street gangs, come on to campus to settle disputes, which are the largest motivation for K–12 incidences.

This also gets to the next cluster of 19%, where the person who pulled the trigger is unknown. Contemplate that for a second. Someone brings a gun onto a K–12 school campus, fires it, and that suspect is never identified. This cluster is quickly followed up by 12% of shooters who had no relationship to the school whatsoever. They were not students, not faculty, not workers or bus drivers, nada.

Foreshadowing just a bit, we see that most of the instances were caused by students, and most of their motivations were for the settlement of grievances.

The “Where”

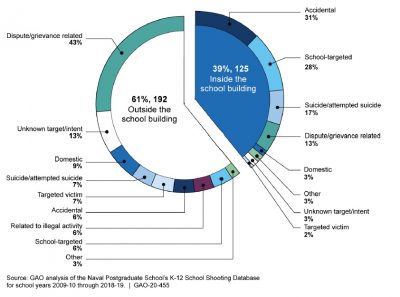

Chart from GAO report on school shootings that breaks down both the motivations/circumstances of why a gun was discharged and if it was indoors or outdoors

Where the shootings take place combined with the motivation gets very interesting. What we see is that the settlement of grievances, the largest motivation for K–12 campus shootings, tends to happen outside of the school building. We noted that a number of people not associated with school or who are unknown come onto campus. The intersection of grievance settlement with students and non-students outside of the school building is instructive.

On the other hand, accidents and specifically targeted shootings mainly happen in the building. The accidental aspect is predictable since people on campus spend most of their time in the building, and if they were to have an accidental discharge it would most highly likely be indoors. And somebody who’s committed to mass murder is going to look for cattle pen scenarios, which means looking for classrooms packed full of students.

This separation of motive versus indoor/outdoor locations is another bit of foreshadowing as we begin to explore the intersections and what possibly constitutes the greatest threat on K–12 campuses.

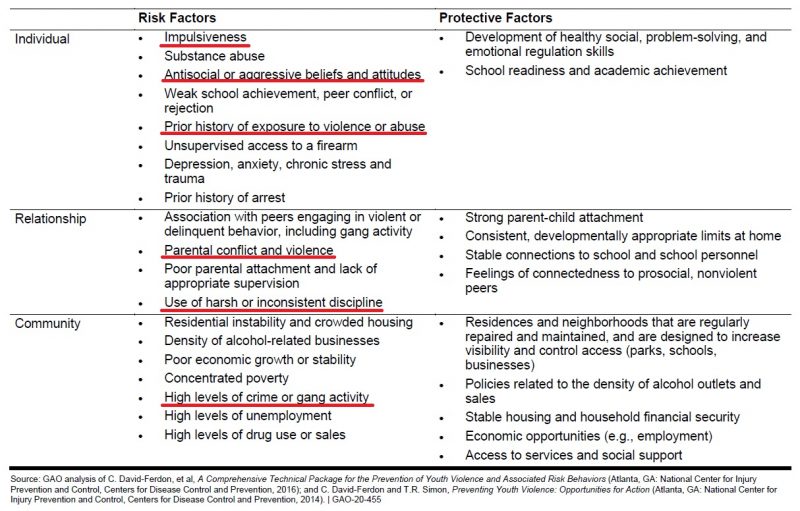

Economists and rational people (which is not to say that all the economists are rational) will tell you that motivation is driven in part by circumstance. The circumstances of shooters are a key to reducing K–12 school shootings.

The most disturbing table within the GAO’s report lists the risk factors and the protective factors that drive public school shooters. Most important on the list is how one comes to their beliefs about violence, which for children and teens in K–12 schools are largely formed by both their parents and their community.

When we look at the relationship row of a specific table in the GAO report, we see what has also been reported by those who study gangs and gang culture. Parents who are disconnected, who are violent themselves, who have poor conflict management skills of their own, or who simply just don’t care about their children much, create children who also are bad at conflict resolution – or worse, who adopt street gang behaviors where violence is how conflicts are resolved.

The Death Divide

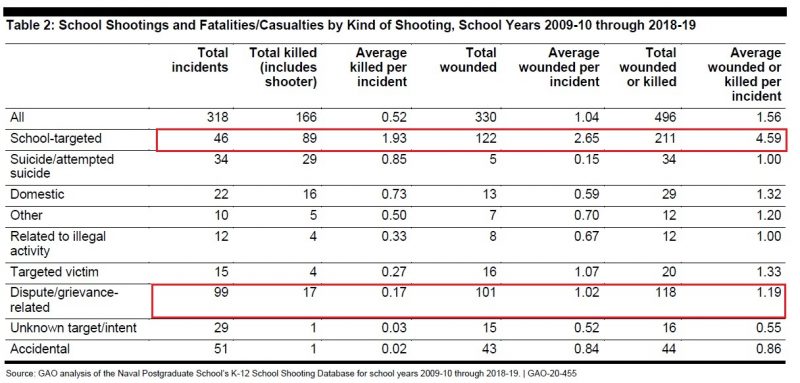

It is worth noting that although dispute shootings, which we suspect are aligned with gang culture, are twice a frequent as school-targeted shootings, while the latter category has a higher average body count. This makes sense for the following reasons:

DISPUTE: Most often one person, acting spontaneously, with a grudge/dispute with one other person, so a limited set of targets and intents.

TARGETED: A generalized grudge against the school/classmates/cliques, which allows for a large number of targets; often planned to “benefit” from classroom and hallways creating a cattle pen scenario.

Sadly, the former is more predictable than the latter and more straightforward to address.

Getting Pointed About K–12 Shootings

From the above associations and the core data, we’re beginning to see a relationship between the type of community and the type of parents and the most frequent causes of K–12 shootings. To put an extremely fine point on it, the probability of a gun being misused on the K–12 campus is strongly associated with inner-city life, inner-city attitudes towards violence, and the influence of street gang culture in terms of the use of violence to settle grievances.

As with street gangs in general, political leaders in major metropolitan areas seem largely disinterested in controlling cultural attitudes towards violence, and this then leaks into K–12 schools within their control.

Comments

K–12 Shooting Stats — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>