Habitual Effects

Repeat offenders in prison are not committing crimes on the streets.

This was proven when in a national revolt over spiraling crime, 24 states passed habitual offender laws in just four years. The effects are compelling.

Take-aways

States with habitual offender laws:

- Incarcerate 73% more violent offenders.

- Reduce violent crime by 85%.

- Reduce homicides by 49%.

The Prelude to Three-Strikes

|

|

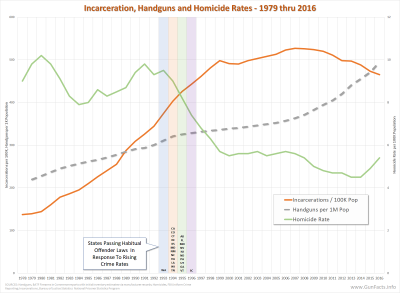

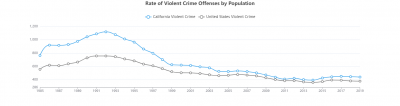

Violent crime was rising across America in the 1970s, 1980s and into the 1990s. Americans got sick of it and launched two of the largest legislative realignments since the end of the Civil War, both with an eye toward controlling criminals.

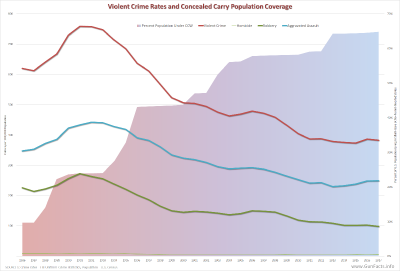

We won’t spend time discussing the expansion of concealed carry, except to note that it started in 1988 in Florida. After it was shown that public carry was not causing harm there, and even greatly dropped some categories of violent crime in the “Gunshine State,” other states flipped to “shall-issue” concealed carry regimes. We cannot confirm that expanded concealed carry contributed to the steady drop thereafter in violent crime, but we can say with certainty that it didn’t make things worse.

But we confirm that locking up criminals did.

The second great legislative reaction was that 24 states passed habitual offender laws (HOLs) in just four years. Those states accounted for 54% of the nation’s population in 1993, the first year of this legislative wave. This is statistically compelling – that over half of the repeat criminal offenders in America were suddenly facing long or even lifetime prison sentences.

And send them to prison America did.

Incarceration rates already were rising before 1993, mainly due to the justice systems focusing on all offenders even without HOLs. Incarceration rates accelerated into the four-year span of new HOLs. But interestingly, violent crime rates remained steady leading up to the wave of HOLs, then started dropping thereafter.

This alone does not prove that HOLs did the trick, but the statistics bear out the theory.

The Plunge

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

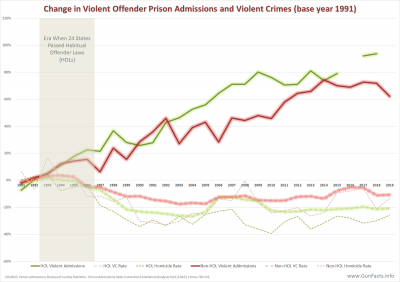

HOL states saw a deeper drop in violent crime, but especially in homicides as HOLs took effect. Keep in mind, all states were “getting tough on crime,” but some passed HOLs to ensure judges and prosecutors did not remain soft on crime. So, even in non-HOL states, there was a drop in violence.

Just not nearly as deep as in HOL states.

HOL states accelerated their violent criminal prison admissions 73% more than non-HOL states. This translated into HOL states seeing 84% more reduction in violent crime rates and half as many homicides.

Curiously, the percentage of incarcerations for violent crimes dropped a little in both HOL and non-HOL states. But as more people in total were being imprisoned, so too were the total number of violent offenders being locked-up.

It was the difference that matters because surprisingly the total new prison admission went up more in non-HOL states – a 33% increase compared to 28% for HOL states. On the whole, non-HOL states were processing more total prisoners, and HOL states were processing more repeat violent offenders. So naturally HOL states enjoyed a greater drop in violent crime.

California’s Three Strikes Law

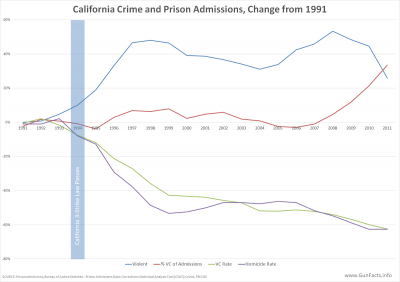

California politicians have of late claimed the 1993-onward drop in violence in their state was attributed to gun control laws.

And they never even mention their 1994 three-strike HOL.

California processed nearly 90,000 people in the first decade of their HOL. 1

That’s a couple of large football stadiums full of habitual criminals.

Before their HOL was enacted, California’s violent crime rate was much higher than the national average. Yet California’s aggressive HOL incarceration rate (up nearly 50% in the first five years) caused California violence to rapidly fall to national levels.

The Odd Bump

Smart readers like yourself noticed that between 2006 and 2008, violent crime in HOL states rose to about the levels of non-HOL states. This bump was odd and has no great explanation because it was attributable to four states.

For this brief period, Georgia, Louisiana, Nevada and Wisconsin saw their violent crime rates worsen. All except for Wisconsin reversed this trend in 2009 and rates resumed falling, exceeding their previous lows. Two states were Southern but not neighbors, one is in the Western region, and one is Midwestern. All have very different geographies, demographics, economies. Assuming that the FBI did not have a data collection fluke for these four states in a three-year window, we’ll have to accept a temporary anomaly.

Data Disclaimers

Like much in life, data is not as complete as number nuts like Gun Facts would like. For example, when you ask the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) for a data table on prison admission by the classification of crime to the state level, the data only goes back to 1991, shortly before the HOL tsunami. In a more perfect world, we would look at a decade of data before and after this legislative transition; but in this case we don’t know if most people entering prison were going in for violent or non-violent offenses before 1991.

Worse still, some states were a bit sloppy about reporting data to BJS. Arkansas, for example, simply did not classify 44% of their prison admissions from 1991 through 1998, resulting in the classification of “missing.” Hence, Arkansas is “missing” from this analysis.

Ten states (Alaska, Arizona, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Montana, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Wyoming) did not report imprisonment data before or into the early years of the HOL enactment spree, DC stopped doing so in 1997, and Massachusetts quit classifying categories after 1995. BJS coded Connecticut as NA, which is a bit of a stumper.

Longish story short, a lot of states were dropped from this analysis due to their data reliability issues. Also, six states had HOL laws long before the 1993 peak (Alabama, Delaware, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Texas) and are excluded from analysis. But enough states (31) remained, 16 (52%) of which were new HOL states and the rest not, so roughly an even split.

Thug Life in the Pen

Keep in mind that HOLs are for habitual criminals, and that habitual means “done or doing constantly.” HOLs then address individuals who make a life of criminality.

Some research indicates that there are links between genetics and aggressive behaviors. There are also subcultures that condition people to accept violence as viable if not glorious. Combine the two and you generate mayhem.

This is the key to the success of HOLs – they target people who are habitually violent by nature or nurture. Since there is no evident redemption created by the criminal justice system, anything less than incarcerating repeat violent predators means that they will return to and harm society.

Notes:

- A Primer: Three Strikes – The Impact After More Than a Decade, California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2005 ↩

2 questions:

Could you help with the definition of “violent crime”? Assuming that is defined differently from state to state?

You refer to the 3 strikes laws but do not define how the violent vs non violent intersect with the “habitual”? Don’t want to assume they’ve been segregated in this… Also in that same vein, is there any correlation between the violent and non violent or does that just muddy up the waters?

1] We used FBI crime data, so their definition of violent crime holds, four offenses: murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.

2a] We are unclear on your second question. In most HOLs (and they vary by state) the combination of strikes are variable. For example, some states may require one, two or all three of the strikes to be violent.

2b] Again, unsure about your question.

I had a cousin that had a long history of violent behavior, mostly linked to his drinking. When CA passed the 3 strikes law any new incident would trigger the 3rd strike.

He cleaned up his act, quite drinking and never even got another ticket until the day he died 2 years ago.

the 3 strikes law worked well with him.