TASSS and Accuracy

There is a lot of public confusion about school shootings. Some of this is intentional, due to data manipulation by activist groups. Some of it is because researchers are highly inconsistent about definitions and approaches.

The good news is that there is a high-quality database that shows us a lot of interesting information about shootings in K–12 schools. The bad news is that the raw data is not publicly available, but we’ll get to that gripe later.

Takeaways

- Media-cited K–12 shooting databases overstate such events by 40%.

- Most K–12 shooting events are in major metro areas and exceed their population-based share.

- Many K–12 shooting events share M.O. profiles of street gang retaliatory action.

- 26% of K–12 shooting perpetrators are “unknown” and not charged.

Reliable Sourcing

![]() A small number of databases have been generated by sundry people and organizations in an attempt to document school shootings. Some of these data sets are marginally acceptable while some are completely ridiculous. Some of these include colleges while others omit them, and some don’t even require a gun to be fired for it to be classified as a “school shooting.”

A small number of databases have been generated by sundry people and organizations in an attempt to document school shootings. Some of these data sets are marginally acceptable while some are completely ridiculous. Some of these include colleges while others omit them, and some don’t even require a gun to be fired for it to be classified as a “school shooting.”

One database 1 that gets a lot of media attention is possibly one of the worst of the lot. We won’t recite all of their sins, but they include so many events that are not actual school shootings that when the federal government used their database as a starting point, and then whittled away those things that were not actual school shootings, 40% of the database went away. 2

That’s what makes the database that we review here 3 of great interest to us. The methodology, scope of data sources, and general robustness of the methodology gives us great confidence in the soundness of the data. The researchers also defined a rather crisp and accurate definition of a school shooting and made sure that all the entries in their database conformed to that definition.

The Perp and Metro Connection

One of the first interesting elements of this database is that most of the K–12 school shootings occur in major metropolitan areas. It is also interesting to note that many of the characteristics of the shooters align with what we see with common street gangs, which as we know are also a feature of major metropolitan areas.

The snap assumption one could make from this is that street gangs, gang culture, or inner-city cultures that condone or tolerate gangs, are foundational to attitudes about violence which then carry into the schools in those same neighborhoods. In other words, most of the K–12 shooting problem may be distinctly associated with inner-city dysfunctions.

Here is one indicator: 56.9% of all K–12 shootings happen in major metropolitan areas. However, those areas have only 30.1% of all K–12 age students. 4 In other words, school shooting rates are about double what the population alone would predict in major metropolitan areas. And as we know from reams of criminology research about street gangs, and survey work done by our own federal government, most gang activity is in major metro areas.

The unknown and unauthorized perp problem

26% of the intentional shootings on K–12 campuses were committed by unknown perpetrators.

Unknown ….

There are a few reasons why a perpetrator might be unknown. He could be a stranger. Within gang-centric communities which have “no snitching” cultures, witnesses may not be pointing to those who they know pulled the trigger. Often within urban areas, people involved in street crime will wear hoodies and some form of face covering to conceal their identity, which would apply to targeted shootings on K–12 campuses.

The key point is that over a quarter of K–12 shootings are done by people who are never apprehended or charged. That the police cannot figure out who the perpetrator was is a major concern. That said, this data agrees with other research 5 that shows that people coming on to K–12 campuses who aren’t supposed to be there are significantly contributing to school shootings.

To foreshadow, we note that inside street gang cultures, retribution killings are very common. It is not a far stretch to say that many, perhaps most, of these stranger-perpetrator K–12 shootings are gang members or gang affiliates coming onto campus and hunting one or more of the students.

The criminal record problem

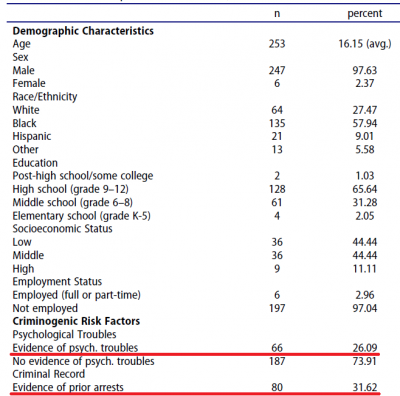

Thirty-two percent of adolescent perpetrators of K–12 shootings had prior criminal records. Using FBI definitions, about 29% of the entire population, not just the adolescent population, has a criminal record. And people who have been out of K–12 education for decades have had many more chances to rack up criminal offenses than somebody who only became a common criminal at age 14 and left high school at age 18.

This means a higher percentage of adolescent school shooters are already criminally minded compared to older people. Stated differently, to rack up so many criminal charges before you are a fully formed adult means that you entered the criminal realm early in life and have been willingly committing crimes. This is far different than people who commit crimes during adulthood out of the “necessity” of economic survival.

Pair that datum with the other elements we’ve discussed so far, and you begin to see a picture evolving. Teens with criminal records, many of them on campuses where they don’t belong, are committing most of the K–12 shootings in major metropolitan areas.

Pair that datum with the other elements we’ve discussed so far, and you begin to see a picture evolving. Teens with criminal records, many of them on campuses where they don’t belong, are committing most of the K–12 shootings in major metropolitan areas.

Twenty-one percent of the adolescent perpetrators, according to this report, had gang associations. This is almost exactly the percentage found for street-gang active ages (14 thru 24) in the Top 15 Murder Counties study we conducted.

But these are known/admitted gang members. There are many members who do not confess to authorities about being in a gang, and a lot more juveniles who are only “associates” of street gangs. Hence, the 21% of K–12 shootings being gang related is a floor, not a ceiling.

The mental health underpinning

Twenty-six percent of adolescent K–12 shooters had evidence of psychological troubles. However, we don’t have a breakdown of this vis-a-vis the kind of shooting they did. As with all mass public shootings, we expect the slope to skew heavily towards perpetrators of those events.

Though the literature is chaotic, the percentage of the population that has some sort of mental health issue ranges between 20% and 26%. What this means is that for K–12 shooters, they are on the high end of the range for mental health problems. There is some literature about the mental health of gang members, but we won’t get into that for now because it’s very narrowly studied, and we are unconvinced of the validity of the data on a national scale. However, that this many K–12 shooters are on the high end of the range for mental health problems is a factor that needs to be considered.

The Relative Dearth of Mass K12 Shooting Events

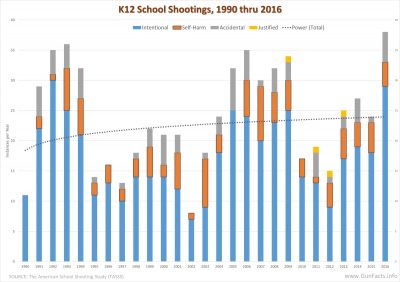

“Only” 3% of K–12 shootings were mass shootings, and that’s using the more generous definition of three or more people killed in the event (the traditional criminology definition of a mass public shooting is four or more killed, not including the perpetrator).

What we’re beginning to see here is a divergence of public understanding and fear when it comes to K–12 shootings. Most of our attention is riveted on the high body count events such as Parkland High School or Sandy Hook Elementary. But statistically, those kinds of events are very rare. The bulk of K–12 shootings appear to be tied to major metropolitan areas (likely inner cities), and likely associated with or related to gangs, or at least suggesting gang culture retaliations.

The Suicide Question

|

|

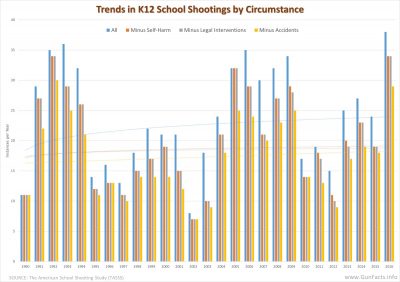

Fifteen percent of K–12 shootings were self-harm events. Within this category are both attempted and successful suicides, which includes not just students, but also faculty or employees.

This begs a question that we’re not going to solve today. The question is whether suicides or other forms of self-harm shootings should be included in a K–12 school shooting database. We at Gun Facts are of a mixed mind. We certainly want to account for all potential damage caused by a bullet intentionally fired on a campus. Even a suicide attempt might result in collateral damage.

On the other hand, nearly all suicide attempts don’t result in harm to others. What most parents are worried about is whether their kid will be the victim of gunfire on their campus. Including suicides gives a misleading indication of the threat.

Our gut instinct is to present the data both ways. First, we would encourage the maintainers of this database to publish the data in separate modes with the same column headings. Mode 1 would be all events. Mode 2 would be all events minus self-harm. Mode 3 would be all events minus self-harm and legal interventions. Mode 4 would be the same as mode 3 but would also remove accidents. This would give everybody a clean view of the probability of a threat to any given school student.

The Database Access Complaint

We have to take a moment to complain.

The raw database for this project is not available to the general public, and not available to the Gun Facts project either. Academics at universities that have gone through elaborate needs justification processes can get access to this data, but nobody else can.

Our favorite self-quote is, “To solve a problem you must understand the problem.” The best way to get an understanding of K–12 shootings is to make sure that all of the data is available to all researchers so that all of the perspectives can be generated and published. We encourage the maintainers of this particular database to find a way to anonymize the data (the common justification for sequestering such is due to privacy concerns for victims and perpetrators) and make the anonymized database freely available.

We’re not going to hold our breath, because academia loves having a stranglehold on inconvenient information.

School is Out for Today

The good news, if we can say anything is good about K–12 shootings, is that statistically they are rare and they are also highly concentrated in major metro areas. This at least makes the problem much easier to address because of its locality and its likely underlying causes.

But we have a hunch that politicians will not do so. The literature on the intersections between inner-city street gang cultures and homicides is well established, and yet politicians in the major metro areas where most of the blood is shed do little or do nothing to address the underlying disease.

Notes:

- Alternately either the K–12 School Shooting Database or the K–12 school shooting database from the Naval Postgraduate School. The maintainer of the former was a graduate of the latter, which explains both the connection and the shared problems with both databases. ↩

- Characteristics of School Shootings, General Accounting Office, 2020 ↩

- The American School Shooting Study (TASSS), Using Open-source Data to Better Understand and Respond to American School Shootings: Introducing and Exploring the American School Shooting Study (TASSS), Journal Of School Violence, 2022 ↩

- Using 2016 Census Bureau estimates, to coincide with the endpoint of the TASSS dataset ↩

- Characteristics of School Shootings, General Accounting Office, 2020 ↩

Comments

TASSS and Accuracy — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>