Fame, Media and Mass Shootings

Why people shoot herds of innocent bystanders in bars, concerts, movie theaters and schools is an area of earnest interest to the Gun Facts project, and to other researchers.

So acute is this interest that the academic journal Criminology & Public Policy devoted their entire February issue to 16 new papers on the topic. The Gun Facts project hopes to read all of them, but we start with a tantalizing and slightly flawed item, Why have public mass shootings become more deadly? Assessing how perpetrators’ motives and methods have changed over time. 1

Not criminology malpractice

This certainly is not a John Hopkins style selection of anti-intellectual tripe composed (allegedly) by doctors pretending to be number nuts. No, this paper is rightful criminology research and the type that the Gun Facts project prefers – namely being devoid of statistical hocus pocus and instead a solid tally of bad tidings.

In short, the authors grabbed a list of mass public shootings that fairly closely matched the one used in the Gun Facts Mass Public Shooting (MPS) database as well as those published by the Crime Prevention Research Center. It covered MPSs going back to 1966 and asked two basic questions: Are things getting worse? And if so, why?

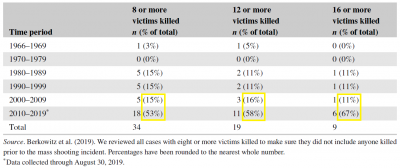

The authors’ most interesting table shows a sudden and sharp spike in the number of MPSs in which large numbers of people were killed in this decade. This is not out of line with what the Gun Facts MPS database shows, but as always, devilish details are involved.

|

||||||||

What makes us ponder deeply is that for the preceding three decades, things were fairly static in terms of high-body count shootings – 30 stable years compared to less than nine highly volatile ones. Much has occurred between 2010 and today – climbing out of a massive recession, major shifts in drug cartel products and importing, and the continued social upheaval the Internet has wrought.

And there was Pulse Night Club, a church in Sutherland Springs, and Las Vegas.

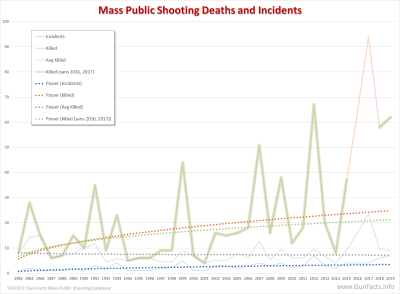

Those and similar events occurred more tightly in the second half of this deadly decade and really skewed the curve. This is non-trivial. The average number of people killed in MPSs in the first half of this decade was slightly less than in the entire previous decade. But the second half of this decade has been horrific. Compare the rolling average of 7.5 people per incident before the half-decade that included Pulse Night Club (49 killed), Sutherland Springs (26) and Las Vegas (58). We have to toss in El Paso (22) as well since it is in the range of this study.

Here is a chart which shows things a bit more visually. The arc for the annual number of people killed in MPSs increases, but you can see how omitting the two most grievous years bends the curve significantly.

This bit of trivia is, well, not trivial and sadly amplifies the main point of this paper, namely that the psychology and preparation habits of mass shooters has changed.

Motivated to murder

In this and more than a few other papers in the psychology field, it is noted that today’s young think fame is important. Not just desirable, but that one is without value unless they have fame. As many in the fields of criminology and psychology have noted, there is a blurring in the minds of today’s younger generation of definitions for “famous” and “infamous,” with the latter being substituted for the former. In other words, to get fame and attention, infamous mass murder is a viable path (especially for those harboring grudges – see our review of the research done by the U.S. Secret Service).

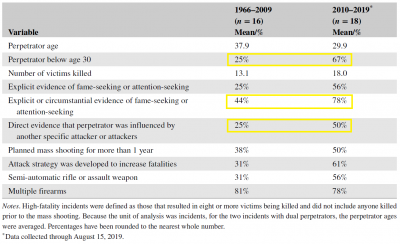

| Variable | Change |

| Explicit evidence of fame-seeking or attention-seeking | 124% |

| Explicit or circumstantial evidence of fame-seeking or attention-seeking | 77% |

| Attack strategy was developed to increase fatalities | 97% |

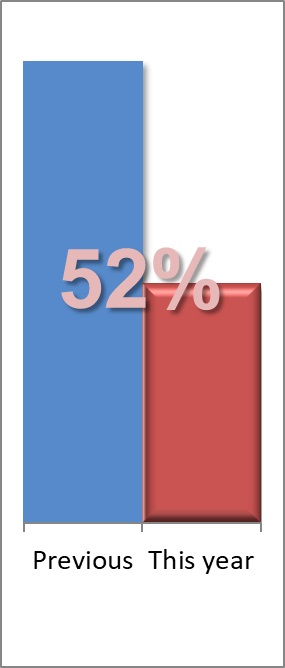

The helps to explain the 168% increase in mass public shooters under age 30 (as a percent of all shooters). That rise, paired with 77–124% increases of evidence in fame-seeking by shooters in recent history, is of keen interest.

The other factor applies to preparation in the pursuit of fame. This and other reviews of the motivations of mass shooters expose that mass shooters study one another. This provides new shooters not only motivation, but it also shows them what works or not in terms of achieving higher and higher body counts. This paper concludes that there is a 32% increase in the rate at which new shooters plan their attacks for more than a year and a 97% increase in those who planned their attacks for maximum carnage.

Recapping: Younger, fame-hungry shooters taking longer to plan, and they plan to achieve new high scores.

[EDITOR: One quick caveat – the numbers in regard to motivations are, per email correspondence with the paper’s lead author, of just the high fatality events, not all MPS events]

Tail wagging the dog

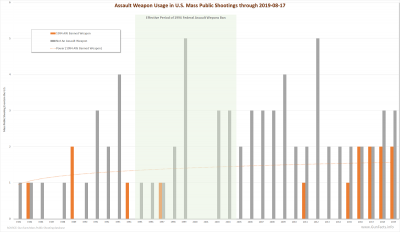

Where this paper stumbled ever so slightly was at the end. The authors let the tail wag their dog when they seemingly sought to find a culprit among the weapons used in MPSs.

The authors incorrectly conclude that “assault weapons” are a major contributing factor to the recent rise in the deadliness of MPSs. But, to their credit, they also clearly state that “public mass shooters who want to produce high death tolls seem to care about having powerful weapons.” Stated a little less academically, if you take a year to plan an attack with the goal of obtaining a very high body count, you will likely plan on acquiring firearms that you think are more deadly.

Where the authors went astray was that handful of post-2014 events that skewed the calculations. As this chart shows, those post-2014 incidents – Pulse Night Club (49 killed), Sutherland Springs (26) and Las Vegas (58), El Paso (22) and others – were relatively new oddities in terms of weapon and location choices (night club, church, outdoor concert). Since guns classified as “assault weapons” have existed for a long time (the AR-15 was introduced to the consumer market in 1963), it is their very recent selection for seven MPSs that is an exception and not a rule (and at least one of those MPSs was a terrorist attack). Otherwise, they would have independently escalated along with the increased frequency if MPS events.

But is that very recent bump in “assault weapons” use meaningful? Unlikely.

The infamous Virginia Tech shooting was done with handguns and using magazines with capacities standard for the guns used. In at least two of the post-2014 MPSs “assault weapons” were below the author’s threshold for “high-fatality” events. Thus the “weapon choice = body count” argument is inconsistent. However, “cattle pen” shootings combined with “assault weapons” is a little more compelling. Of the post-2014 MPSs, the five highest body count events – between 17 and 58 killed – were well planned events where both a cattle pen scenario and a 1994 banned “assault weapon” were employed. Indeed, the authors caught wind of this when they reported:

“The 2012 Aurora shooter wrote that he selected a particular movie theater because it would have many people “packed in [a] single area” and he could lock its doors, so his mass shooting would result in ‘mass casualties.’”

Planning, planning, planning.

Bloopers

This otherwise serviceable paper brought more than a few guffaws around our office.

We won’t assume bias in the authors, but their misuse of basic technical terms is disconcerting. They refer to suppressors as “silencers” and report on the number of “assault rifles” being manufactured whilst discussing semi-automatic consumer rifles. These are not cardinal sins, but enough to earn a short stint in gun criminology purgatory.

Good to know

The key value of this paper is in its extended insights into the changing demographics and motivations of mass shooters. It also adds to the ongoing understanding of the “media contagion effect,” which may be largely driven by social media.

| CNN | 1980 |

| HLN | 1982 |

| Fox | 1996 |

| MSNBC | 1996 |

| 2004 | |

| 2006 | |

| 2010 |

That last point is speculative, but worth pondering. This table shows when some of the more notable “always on” media came to life. If all media contributed equally to the increased desire to commit mass murder, then large-scale killing would have scaled upwards long ago, in the 1980s. But the youngest generations are not turned on by television (and vice versa), relying instead for the peer-level stimulation of online media. Many of the recent younger killers, from Isla Vista to Parkland, used social media for advertising their grievances and manifestos. It may be this individual broadcast mode that drives some of them to plan their rampages carefully.

Notes:

- Why have public mass shootings become more deadly? Assessing how perpetrators’ motives and methods have changed over time.; Lankford, Silver; 2020, Criminology & Public Policy ↩

It’s nice to read an article that attempts to address the underlying root cause of mass shootings rather than simply blaming the abundance of firearms or a specific type of firearm. The fact that the shooters are progressively getting younger is a disturbing trend. They also tend to telegraph intent via social media. But more troublesome is the fact that they study previous mass shootings. Spending more time planning makes a much stronger case for the higher body count than the type of firearm involved.

I debate with gun grabbers on social media all the time, and frequently point to the Virginia Tech shooting as evidence that the type of firearm used and magazine capacity are not significant factors in increasing the body count during a cattle pen shooting.

Keep up the great work!