Mental Mass Contrast

It is well established that most mass public shooters (MPS) have mental health problems. The question is whether they are more prone to instability than the public and by how much.

The answer is upwards of nine times as unstable.

Major Take-aways

- Depending on the subtopic, MPSs are 1.4 to 9.0 times more likely to have mental health problems.

- Most commonly, they have “thought disorders” – a characteristic of psychotic mental illness – at nine times the rate of the general public.

The Violence Project and Their Book

We have discussed the Violence Project and mental health before. They study MPS due to significant funding (for which we are green with jealously) and unprecedented access to uncommon data. They have produced the most comprehensive database on MPS available. The Gun Facts project will continue to maintain our mass public shooting database because we track important variables that the Violence Project does not.

They have a book out that is a solid distillation of the findings, though we warn the reader that some statements they make are not great analysis. They appear to purposefully distance themselves from conceptual landmines and potential controversy. This does not weaken the value of their book, but it raises BS detectors and doubt about some of their conclusions.

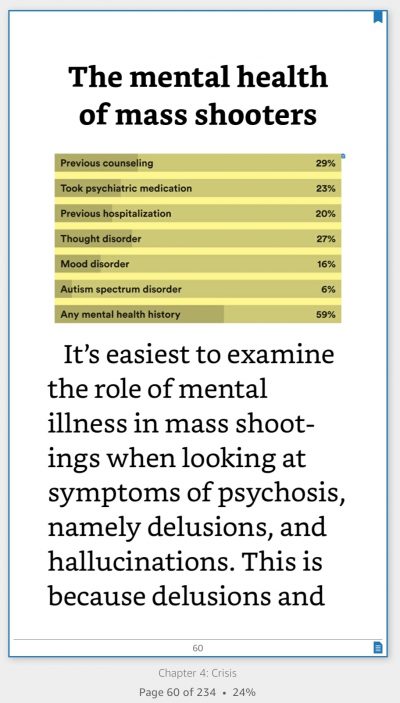

Most notable, their database provides the deepest dive into the backgrounds of shooters, including a rather complex set of information on their mental health or lack thereof. Many more details are provided, such as this handy breakdown of mass public shooter mental issues.

But the authors erred in their prose when, like so many others, they belabored the point that though mental illness is common among mass public shooters, mass public shootings are rare among the total population of people with mental health issues.

To which we say, “So what?” Proper analysis begins with defining the population under study (e.g., mass shooters) and then explores the commonalities. To reframe the discussion away from the study population is to “look down the wrong end of the telescope.” Sure, you’ll see something, but it will be a distorted image that will lead you astray.

This perspective problem leads to the question, “Is mental illness more prevalent in mass shooters than the general public, and if so, by how much?” The Violence Project does address this question, but we decided to make the information a bit more usable.

The Core Data and Public Comparison

What we see is rather stark and frightening.

| General Population | Mass Public Shooters | Multiple | |

| Previous Counseling | 9% 1 | 29% | 3.2 |

| Psychiatric Medications | 16% 1 | 23% | 1.4 |

| Previous Hospitalization | 4% 4 | 20% | 5.0 |

| Thought Disorders | 3% 2 | 27% | 9.0 |

| Mood Disorders | 10% 3 | 16% | 1.6 |

| Autism | 1% 5 | 6% | 6.0 |

| Any Mental Health History | 26% 6 | 59% | 2.3 |

- 1: Mental Health Treatment Among Adults: United States, 2019; Terlizzi, Zablotsky; CDC – NOTE: 19% had received some form of treatment, but not specifically psychiatric counseling

- 2: Thought Disorders and the Non‐Psychiatric Provider; Bryan; 2019 WNA Northwoods Clinical Practice Update

- 3: Any Mood Disorder; Nation Institute of Mental health; 2001-2003

- 4: Hospital Stays Related to Mental Health, 2006; Saba, Levit, Elixhauser; Agency for Healthcare research and Quality; – rate derived by dividing admissions by population, so possibly overstated

- 5: Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample; Kim, Leventhal, Koh, Fombonne, Laska, Lim, Cheon, Kim, Lee, Song, Grinker; National Institute of Health; 2011

- 6: Statistics related to mental health disorders; John Hopkins Medicine

The big item is “thought disorders,” which the American Psychological Association defines as “a cognitive disturbance that affects … thought content, including poverty of ideas, neologisms, paralogia, word salad, and delusions. A thought disorder is considered by some to be the most important mark of schizophrenia, but it is also associated with mood disorders, dementia, mania…”

Mass public shooters have thought disorders nine times as frequently as the general public.

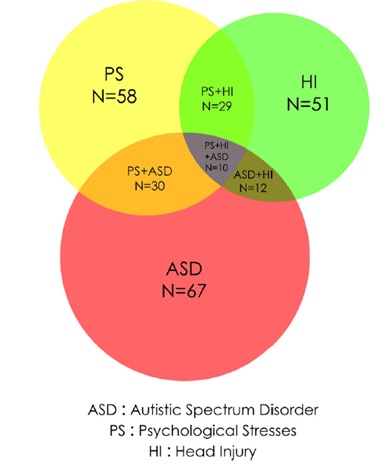

The second most exaggerated mental health disorder among mass shooters was being on the autism spectrum, with mass shooters being six times more likely to be autistic than the world at large. As we discovered in one academic survey of literature, being on the spectrum is the single most common mental impairment of mass murders and serial killers.

The second most exaggerated mental health disorder among mass shooters was being on the autism spectrum, with mass shooters being six times more likely to be autistic than the world at large. As we discovered in one academic survey of literature, being on the spectrum is the single most common mental impairment of mass murders and serial killers.

Most troublesome, from the public policy perspective, is that mass public shooters had previous psychiatric hospitalization rates five times higher than the public in general, but their potential for causing great harm was either [a] not identified while hospitalized, or [b] treated in a blasé way using medications, which mass public shooters swallowed at a slightly higher rate than the rest of us.

What is not known is whether mass public shooters stayed on their meds. A person with thought disorders is likely to be far less reliable than your oddball cousin in taking their medications faithfully. Multiply this danger by the fact that “cold turkey” withdraw from many/most psychotropic medications can produce dangerous states of mania and agitation, along with delusions, hallucinations, and more.

Psychiatric Malpractice

While we are berating the mental health industry, let’s note that mass public shooters were more than three times as likely to have had previous mental health counseling than the masses. An argument has been proffered that people “on the edge” of committing these horrendous crimes are not getting treatment. But with 3X the rate for counseling and 5X the rate for hospitalization, this argument is at best weak if not outright false. Mass shooters are getting treated, but they are also getting released into the wild, possibly without adequate supervision and with drugs that if incorrectly taken may amplify dangers.

What we have is a failing mental health system.

What we have is a failing mental health system.

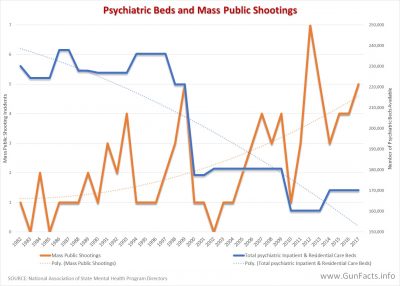

Since the early 1990s, before the Columbine Massacre (which involved “cold turkey” withdraw from psychotropic medications), the number of psychiatric beds has been cut by about 30%. Instead of prescribing confined treatment, the industry has turned to drugs. This, of course, is not the only contributing factor, but it cannot be ignored, and the psychiatric community should not ignore it either.

UPDATE: Psychosis

A 2022 paper concluded that 31% of mass public shooting perpetrators experienced psychosis that played a role in their murders 1 whereas less than 3% of the general public ever develops a psychosis in their lifetime 2

Much of the crime and violence problem in the US today is directly attributable to the justice/medical systems using “the streets” as “extension prisons/clinics,” while simultaneously rendering the general public incapable of personal defense against the inmates.

Theoretically at least, prison serves three purposes: punishment, rehabilitation, and quarantine. Psychiatric confinement serves the latter two. Our rulers have taken to underestimating the value to society of quarantining threats to the common citizen, and our violence problem is the result.

I have only one concern with “improving” the Mental Health System. That is over-reaction and abuse. I rate this as a singular problem, because the two are inter-connected. By “over-reaction” I mean that people diagnosed with a disorder might be confined even though they are “High Functioning”, which is to say exhibit minimal symptoms with absolutely no indicators of violent tendencies, “just to be safe”.

Followed by abuse, wherein family members and other concerned parties, over-represent the symptoms or indicators to care givers to pass on a perceived problem to someone else, which could lead to over-reaction by Mental Health Providers.

Either could lead to an unfair adjudication of mental deficiency, which is the real concern. The affected would have little means or opportunity to oppose the petition, due to their perceived shortcomings. While some might think this knee-jerk, we only have to look as far as the recent case of Brittany Spears, except without the massive funding to provide for “care”, such as she had.