Red Flags

Are red flag laws effective, or should politicians be flagged for being offsides?

Take-aways

- Too few data points for statistical robustness

- Largely irrelevant to homicides

- Barely effective on suicides

- For suicides, “studies” thus far count only “firearm deaths” instead of all forms of suicides, which is a grave methodology error

- Trade-off between a few lives saved and significant due process questions is out of balance

Wave Your Flag

“Red Flag Laws” (RFL herein) are all the rage these days, with many states enacting or considering them. However, the relative newness of RFLs makes analyzing their effectiveness a little tricky.

Before 2016, only two states – Connecticut and Indiana – had RFLs. To see before-and-after effects of any law, you need a little runway (we at the Gun Facts project think ±5 years is sufficient). Most states with RFLs have less than three years of experience with these laws. So, with only two data points, we have to grab a salt shaker, because any analysis will require more than a grain or two.

What we have with the two RFL states poses a bit of a quandary. First, the states are very different in nature. Connecticut, in the Northeast, has a high population density (741 people per square mile), while Indiana is a relatively low-density state (187) in the Midwest. Very different cultures, very different neighboring states, and likely very different gun ownership rates. 1

We also have to take into account that the laws, as enacted, are functionally very different:

Indiana: seizure of a person’s firearms if a police officer believes the person has a “mental illness” and is “dangerous,” defined as an imminent or future “risk of personal injury” to self or others.

Connecticut: requires an “independent investigation” by police if they believe that a person poses “a risk of imminent personal injury” to self or others; followed by a warrant request, with several formal checks on the judge’s ability to order the seizure and retention of firearms by law enforcement.

As you can see, in Indiana a person can be disarmed by the assessment of one cop, whereas in Connecticut it requires a fair bit of process. Between culture, population density and the laws themselves, we can expect some differences between these two states. But can we expect differences between these states and the rest of the country? The answer seems to be “yes,” but turns out to be “not really.”

Let’s Be Dismissive About Homicides

The twin claims about RFLs is that they will lower suicide rates and prevent homicides by hotheads and lunatics. It is the claim about homicides that we can dismiss.

As the Gun Facts project maintains, we are interested in keeping guns out of the hands of terrorists, criminals, lunatics and hotheads. It is these last two groups who are the target of RFLs. The question is, what fraction of the gun owning population are these people? Quite small, actually.

- About 4% of the population has a severe mental illness. 2

- Common estimates are that 40–50% of households own guns, or about 50 million households, on the low end.

- Combined, that is about 2 million severely mentally ill people possibly in the proximity of a gun. But …

- Not all mental illness results in violent behavior

- Families with a member who is mentally ill are much more likely to avoid owning a gun; or at least they would lock it up. The rate, however, is not known.

Two million people – tops – who are mentally ill and might have access to a gun compares somewhat favorably to the number of street gang members in the United States – which, based on the major metro estimates we have stumbled upon, is likely around the two million mark as well. And we know street gangs have guns, know how to use them and employ them daily.

The point is that identifying a person with a violent mental illness, who has access to a gun, and who fits an RFL criteria, is a rapidly shrinking number. Hotheads are even tougher to corner because of the subjectivity of evaluation (a shrink has a standard set of tools and definitions for a severe mental illness, whereas a patrol officer lacks the same for hotheads).

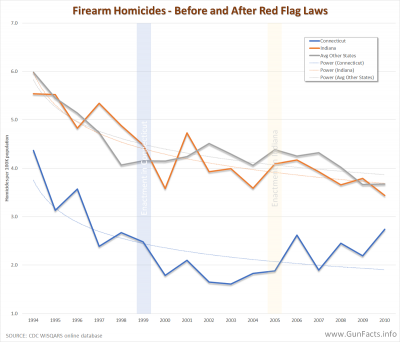

But we at the Gun Facts project hate too much speculation, so we did a quick visualization of the before-and-after for our two RFL states – Connecticut and Indiana. Connecticut saw no lasting change in their homicide rate, and the temporarily lower rate of firearm homicides is more directly explained by the rapidly falling rate of such before the enactment of their RFL. Compared to the states without any RFL, Indiana did no better or worse. This speaks to the notion that:

But we at the Gun Facts project hate too much speculation, so we did a quick visualization of the before-and-after for our two RFL states – Connecticut and Indiana. Connecticut saw no lasting change in their homicide rate, and the temporarily lower rate of firearm homicides is more directly explained by the rapidly falling rate of such before the enactment of their RFL. Compared to the states without any RFL, Indiana did no better or worse. This speaks to the notion that:

- The number of lunatics and hotheads tends to be small (especially compared to gang members).

- Proactively identifying them is subjective, sporadic and loaded with false negatives (people assumed to be agitated but actually were not, or not prone to homicide when cranked).

Suicides, however, are a bit more interesting. Sadly, the science+media ecosystem has already been polluted.

Suicide (analysis) Is Painless

First, let us take to task researchers and some members of the media for ignoring the obvious (the former intentionally, the latter from a lack of journalistic due diligence).

As the Gun Facts project has noted (again, and again, and again, and …) people are very creative in how they kill themselves. In short, if a gun isn’t available, other methods are. In the psych and criminology fields, this is called “substitution of means” and thus there is no correlation between gun availability and suicide rates.

Some researchers have published on how RFLs have reduced just firearm suicides but conveniently sidestepped the substitution-of-means equalizer. Here is a hypothetical situation, for illustration’s sake. Jim is seriously depressed. His wife left him, due to his drinking, which led to him being fired. And he’s ugly. His friends know Jim owns a gun, so call the cops, and they take his gun from him. But Jim also has his estranged wife’s prescription medication she left behind, so he cracks open a fresh bottle of gin and proceeds to swallow every pill he can find. Jim is just as dead as if he had shot himself. Given the vast variety of common substitution of means, no self-respecting researcher would publish on just firearm suicides in relationship to RFLs.

And every reporter should see through that. But the researchers debased themselves, or the reporters didn’t drink enough java to focus on the underlying elements in a press release, and thus caused too many people to believe RFLs made a significant difference.

Sigh.

Due to substitution of means, the overall suicide rate is what needs measuring. The theory at play is that the taking of the gun was not what might have stopped a suicide, but the human intervention and any mental health treatment that follows might. After all, when you are depressed and think the world has disowned you, having a few folks show up and try to rescue you might be enough. Jim might not swallow the pills after all when friends, family and cops try to help.

|

|

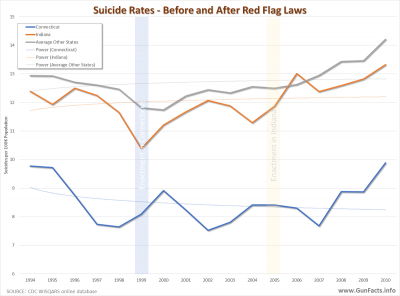

Sadly, this is not the case, by and large. Connecticut had an admirably low suicide rate before they enacted their RFL, which kinda makes you wonder why they bothered. Indeed, were it not for the sudden drop in the state’s suicide rate two years before their RFL was enacted, there would be no downward slope at all. In fact, their suicide rate is higher after their RFL was enacted (we note that the uptick in Connecticut’s suicide rate corresponds with the start of the Great Recession – if we assume the spike is caused by that, then Connecticut’s suicide rate was fundamentally flatlined throughout the post-RFL years).

In a similar vein, Indiana’s suicide rate closely tracks those states without RFLs, both before and after the passage of the law.

There are differences, as statistically uninteresting as they may be. In the case of Connecticut, they had declining suicide rates before and after their RFL was enacted. But the rate of decline was much less afterwards. With suicides rising nationally after the year 2000, both RFL states saw impairment to their suicide prevention efforts.

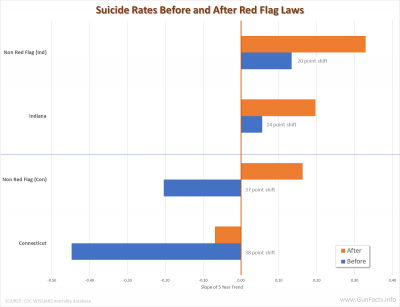

In Connecticut, there was a 38-point shift in the slope of the line from before and after passage, and there was a 37-point shift nationally. In short, their RFL made no difference.

Indiana was a shade more hopeful, but only a shade. Whereas non-RFL states shifted 20 suicide slope points between the five years before and the five years after Indiana’s enactment of their RFL, Indiana shifted 14. Not as large of a move as nationally. But their rate of decline in suicides before their RFL was enacted was smaller than non-RFL states, and their increase after RFL enactment was lower as well. Yet the sift in the slope of the lines between Indiana and non-RFL states was significant but not huge – 14 and 20 points respectively.

What does this really mean in terms of life and death? Not much. In the year Connecticut passed their law, a little over 100 people shot themselves dead. Seventeen years later, about the same (yes, their population rose 5% during that period, so the tiny reduction means something). Likewise, Indiana’s population rose nearly 7% since they enacted their RFL law, but the number of people who killed themselves with a gun went up 45%.

| Year Enacted | 2017 | |

| Connecticut | 111 | 109 |

| Indiana | 416 | 604 |

Now contrast the latest total for those two states – 713 firearm suicides – with the 14,542 firearm homicides, largely gang-related, in the most recent year.

Not entirely useless

There are significant constitutional due process issues with RFLs… expect them to be litigated for years to come. Ignoring that, we can say with safety that from an effectiveness standpoint, RFLs do little. We won’t say “nothing at all.” But the serious trade-off between a robust deference to due process and the small number of lives RFLs might save is distinct.

Notes:

- Many criminologists have attempted to estimate the gun ownership rates by state, and they readily admit their findings are suspect, though criminologist Gary Kleck’s paper contrasting the sundry approaches and showing some alignment of measurements shows we might be able to ballpark it. ↩

- National Alliance on Mental Illness website ↩

This is SO gun-nut!

Here is what the red flag law might prevent:

The shooting occurred about an hour after Hanlon was cited by authorities for having an aggressive animal. In an audio recording regarding that incident, an animal control officer and Hanlon can be heard talking about a fence separating his property from Dolce’s, the affidavit states.

It also says police responded to an altercation between Dolce and Hanlon more than a month before the shooting.

Dolce told police “his neighbor was trying to get him to fight and that there were ongoing issues with the neighbor,” the document said.

You lost all efficacy when you used the label “gun-nut”.

Move along Doug and take your labels with you.

Why “Red Flag Gun Laws” are UnConstitutional and dangerous:

1. There is NO conviction required to confiscate the gun owner’s firearms.

2. There is NO arrest of the gun owner being accused.

3. There is NO indictment of the gun owner being accused.

4. There is NO notification that the gun owner’s firearms are about to be confiscated.

5. The police show up at your door and steal/confiscate your firearms with NO due process!

Yup, that about sums it up! Kiss “presumption of innocence” goodbye. Mind blowing how states can pass a law that absolutely turns a blind eye to the 4th,5th,6th and 14th Amendment in one fell swoop. Did I miss something or wasn’t there something about these government representatives swearing to defend the Constitution? We should be seeing a lot more headlines about treasonous State and Federal representatives.